Final offer arbitration

An intriguing concept rarely used in international practice.

What is it?

Final offer arbitration essentially follows the ‘game theory’ concept.

Two (or more) parties blindly put forward a proposal, consisting of the amount and terms they are willing to offer in the resolution of the dispute. The arbitrator(s) must choose between these offers.

The more unrealistic an offer is, the more likely the arbitrator will choose the other offer. In theory, therefore, both parties are incentivised to put forward a reasonable offer.

Given that less time will be spent on convincing the arbitrator(s) through either verbal or written arguments, as well as the fact that arbitrators do not need to write their own awards, final offer arbitration should result in reduced time and costs.

Where is it used?

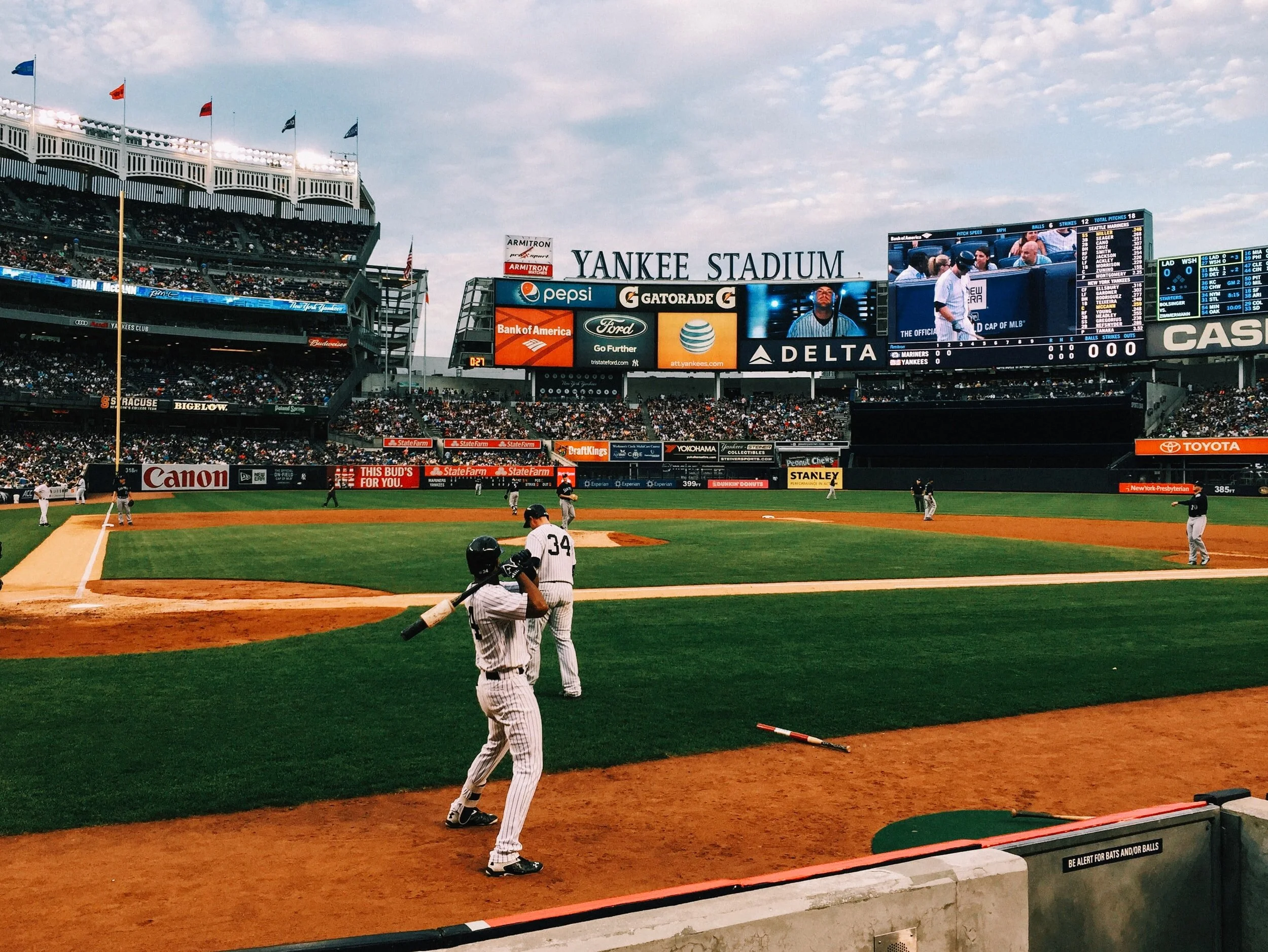

As stated, the concept is rare, if virtually non-existent, in international practice. However, the concept has gained some popularity in the US, where it is used to resolve Major League Baseball disputes, for example in relation to players’ salaries. This has led to its nickname: baseball arbitration. It has also been used to resolve disputes between US states and unionised employees.

Why is it not more popular?

One particular issue sticks out.

In a case where the Respondent does not admit to any fault, it may feel that the right amount it should pay is $0. The Claimant will have a higher amount in mind, let’s say $100 million. If both parties put forward these amounts, the arbitrator(s) would have to choose between $0 and $100 million, which is similar to deciding in either Claimant or Respondent’s favour during a ‘regular’ arbitration.

One could argue that the Claimant and Respondent would not put forward these figures but rather be incentivised to compromise. A Respondent who would usually win on the merits may feel pressured to put forward a $50 million offer as this is more likely to be selected than a $0 offer, and which it still prefers over paying $100 million. Therefore, final offer arbitration may ‘twist’ the arm of a genuinely ‘innocent’ party into paying. This may lead to trigger-happy Claimants invoking arbitration clauses to a greater extent than usual. Of course, this oversimplification leaves aside the evidence, which will certainly guide how both parties will act and what the tribunal will decide.

Nonetheless, following this line of thought, final offer arbitration might be most suitable where the Respondent acknowledges some kind of fault and wishes to settle. However, in such a case, it is hard to understand why the Respondent did not settle prior to the issuance of the final award.

It should be pointed out that even in the case of a $0 vs $100 million offer, where the tribunal is effectively choosing between the Claimant and Respondent, the situation may still be advantageous compared to ‘regular’ arbitration. Each party will have written an award justifying the sum, and the tribunal must choose between them. This should save time and money.

Nonetheless, this may also lead to issues. Any such award is likely to be fairly one-sided, with the other party’s arguments likely only addressed in order to be debunked. Hence, such an award could not fulfil the arbitrator’s mandate to address every relevant issue of the dispute. It cannot be used as evidence that both parties have been heard.

Furthermore, in some countries, such as Italy and Spain, enforcement is only possible where the arbitrator has clearly set out its reasons for the decision in the award. If proposals are accepted as is by the tribunal, without any further commentary, the award might be challenged at the seat of the arbitration - especially if those courts see an issue regarding its recognition and enforcement further down the line.

It is worth noting that certain forms of final offer arbitration permit arbitrators to choose parts of both parties’ proposals and add their own commentary. Whilst this would improve the aforementioned challenges, it does take away from the purpose of final offer arbitration, given that additional time and costs would be incurred. It would also mean that neither amount offered by the parties will be chosen in their entirety, reducing the incentive to propose a reasonable overall offer (although it still exists in relation to individual segments). Nonetheless, it may be a worthy compromise.

In any event, parties can take certain actions in advance to stave off later problems, such as defining the remit of the tribunal, waiving the right of appeal against the award, and agreeing on the procedure and contents of the award.

Despite its challenges, the benefits of final offer arbitration are not to be understated. Arguably, counsel and quantum experts occasionally defend extreme stances during proceedings, as tribunals will often compromise awards halfway between the parties’ demands. The game theory thus clearly also plays a role in ‘regular’ arbitration and there is no way around this. Amending the rules of the game may positively affect the costs of the proceedings. Unfortunately, however, the current system is simply not built to accommodate it: there are too many hurdles in place.